On June 16, 2025, a long-awaited moment unfolded in Libreville. President Brice Oligui Nguema, joined by African Development Bank (AfDB) President Akinwumi Adesina, officially inaugurated the PK5 water pumping station in the northern zone of the capital.

More than a ribbon-cutting ceremony, the event signaled the end of a crisis that had lasted over a decade for seven urban communes. For more than 300,000 people in Libreville, Owendo, Akanda, and Ntoum, it meant the restoration of a fundamental right, access to clean water.

More than a ribbon-cutting ceremony, the event marked the end of a water crisis that had burdened over 300,000 residents in Libreville, Owendo, Akanda, and Ntoum for more than a decade.

The total investment for the PK5 water station reached €117,400,000, equivalent to 77,001,037,800 FCFA. The funding structure was led by:

-

The African Development Bank, which contributed €75,400,000, or 49,465,191,800 FCFA,

-

The Africa Growing Together Fund, which added €42,000,000, or 27,550,194,000 FCFA,

-

And the Gabonese Government, which provided logistical, regulatory, and on-ground operational support (though financial contributions were not disclosed in euro terms).

With a service capacity of 57,600 cubic meters per day, the facility can provide enough clean water for approximately 128,000 residents directly, while extending benefits to over 300,000 people through downstream pipeline and public standpipe connections.

Before the project’s commissioning, many districts relied on water delivered by tanker trucks or had to walk several kilometers to fetch water manually. In these areas, the cost of a single cubic meter of water via informal delivery could reach 10,000–15,000 FCFA, compared to the regulated SEEG rate of 470.97 FCFA/m³ (as of October 1, 2018). This extreme disparity placed immense financial and physical pressure on low-income households and contributed to long-standing public frustration.

The public health implications of the new station are far-reaching. Clean, pressurized water now reaches schools, health centers, and homes, where it supports hygiene practices and helps reduce the prevalence of waterborne diseases like typhoid, cholera, and dysentery. Gabon’s Ministry of Health estimates that poor water quality was previously responsible for up to 20% of child hospitalizations in Greater Libreville.

From an economic standpoint, this infrastructure helps reduce fixed costs for thousands of small businesses. Restaurants, bakeries, dry cleaners, and small manufacturers, particularly in neighborhoods like PK5, Avorbam, and Nzeng Ayong can now operate more efficiently, with reliable access to water eliminating their reliance on costly alternatives. Preliminary estimates suggest a 25–30% reduction in operating costs for water-reliant SMEs in the area.

On the technical front, the project is noteworthy. The PK5 station is equipped with high-capacity pumps, automated filtration systems, and is integrated into a 150-kilometer reinforced water network. More than 60 public standpipes were installed in peri-urban communities, ensuring access for families that still lack direct household connections. The project includes digital monitoring systems for flow rate, pressure, and quality metrics, enabling better system responsiveness and accountability.

The symbolic weight of this project cannot be overstated. For too long, clean water was a luxury in parts of the capital. Now, the PK5 water pumping station signals a shift: water is a right, not a privilege. It also demonstrates what is possible when multilateral financial institutions, national leadership, and international partnerships align around shared development goals.

|

|

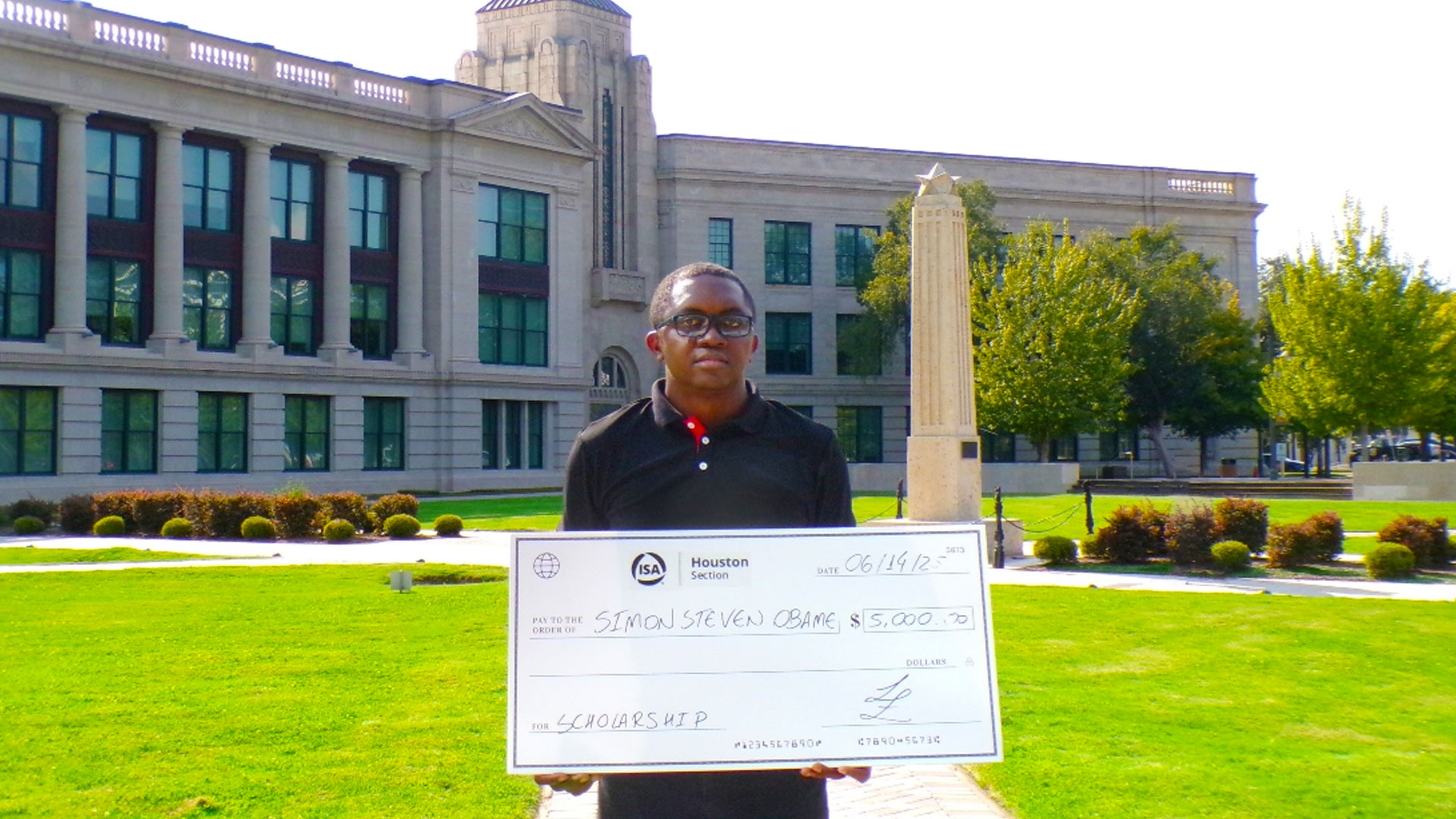

Steven OBAME